In 1913 Elizabeth Evans (23) sailed from Liverpool to India to marry her fiancé in Bombay Cathedral. In the winter of 1923 Geoffrey (9) raised the alarm after witnessing a boat capsize in rough seas off the coast of Cornwall. On a sunny day in August 1942 Maureen (8) was playing in the sand in her seaside village. A low flying German plane bombed and machine gunned the beach killing two adults and Maureen’s six-year old friend. In 1944 RAF bomb-aimer Alun was hospitalised with appendicitis. The training flight he should have been on crashed killing the crew of seven and a lorry driver. In 1973 John’s teenage children observed their dad in his pyjamas wandering aimlessly in the garden at 3am.

The relatives of the people in these unrelated events discovered these stories decades after they took place. They may not seem much in the grand scheme of history. But they had a profound effect on the people and families who experienced them. And possibly shaped their future. Understandably, the individuals in these scraps of history were reticent about talking about their past. Their children and grandchildren grew up not knowing their parents or grandparents were heroes, survivors, adventurers or witnesses to horrific events until much later. Sometimes, well after their relatives had died.

While Samuel Pepys, Virginia Woolf, Ann Frank, hundreds of Edwardian ladies, and the fictional Bridget Jones diarised the minutiae of their lives, chances are any diaries from your parents or grandparents contain mundane scratchings noting doctor’s appointments, bridge nights, play dates or birthdays. We just don’t do diaries anymore.

The Plains Cree First Nations in North America have an oral tradition that keeps their culture and history alive. They even have individual names for specific types of stories. Acimostakewin describes a regular story about everyday events, current news or personal experiences. Atyayohkewina are sacred stories or legends. Most of the modern world has no such tradition.

Capturing a family’s acimostakewin can be a labour of love for some and an unwanted obligation for others. Some don’t care either way. But it’s never been easier to research and document a family’s history. Just Google ‘family history’ and you will be presented with hundreds of pages of genealogy sites. Even the BBC has on-line tools and advice to help you get started. Tracing your family tree, though, is the easy part. The essence of family history is much more than the cold facts of births, deaths and marriages. The beliefs, experiences, relationships and ways of life of your ancestors is what made them. And almost certainly influenced the way you are today.

Social media sites such as Instagram, on-line self-publishing tools, military and newspaper archives, photo diaries, and the ubiquitous smart phones that can snap moments of history in an instant, have replaced the hand-written diaries of the past. They offer an opportunity to search, record and save events and stories, as well as the chronology of your family.

Is it important? American writer James Baldwin said, “Know from whence you came. If you know whence you came, there are absolutely no limitations to where you can go.” And who is interested? If you believe the maxim ‘truth is stranger than fiction’ family stories are arguably more interesting than any fantasy on television, radio or in print. More than 5 million listeners tune in weekly to the BBC Radio 4’s ‘The Archers’. An immense following for what was billed as ‘an everyday story of country folk’. Would our own true lives generate such interest?

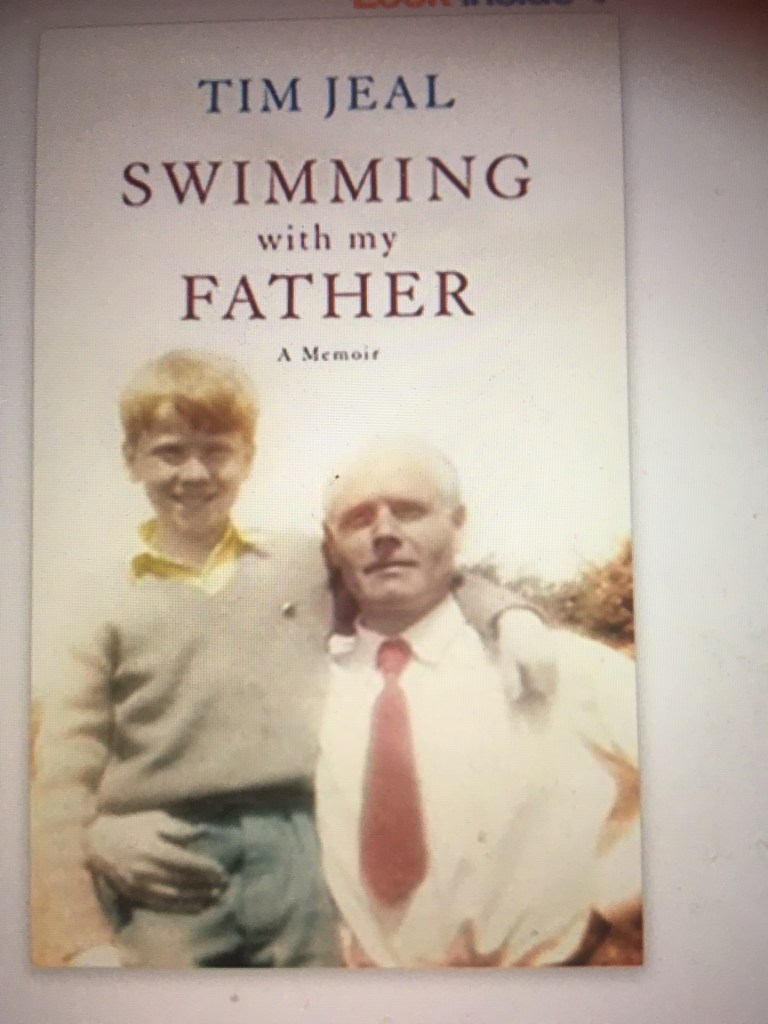

Tim Jeal, noted historian, biographer and author, wrote about his unconventional dad in ‘Swimming with my Father’. “I felt that my eccentric father, who had never done anything truly remarkable, yet was remarkable nonetheless, deserved to be remembered,” said Tim when asked what motivated him to write the book. He continued “Several publishers turned down the finished book because – though finding it funny, well written and true – they doubted whether they could sell many copies of a memoir recalling an unknown non-celebrity.”

Elizabeth’s grandchildren were oblivious to their granny’s adventures until after she died. Her granddaughter, Carolyn, began researching Elizabeth’s life long before the advent of the Internet. Piece by piece snippets of information from letters, crumpled photos and tattered travel documents, came together. Hours spent in the local library with musty old newspapers, photo archives and micro-fiche is probably why more people didn’t bother delving into their family’s past.

For Carolyn, the findings painted a vivid picture of an adventurous woman from rural north Wales, who made a hazardous three-month journey on a troop ship for love. Who lived in a rural mining area in India for six years, then moved to South Africa for four. Hard to equate that bright young voyager with the silver haired granny that Carolyn remembers.

Young Geoffrey grew up rarely mentioning that he had played a part in the rescue of the boaters. Many of his friends only learnt of this heroic act at his funeral.

Maureen never forgot the terrible day when her little friend was killed on the beach. He came from London. His parents had sent him to Cornwall for safety from the bombings. Maureen continued to put flowers on his grave until she succumbed to dementia at the age of 82, and died shortly after.

Alun was guilt ridden at the loss of his comrades. He lobbied for years (successfully) to have a memorial built at the crash site in the north of England. He and his family made an annual pilgrimage from South Wales to the memorial to honour his friends until his own death in 2017 at 94. Before he died he published his memoirs, A Torn Tapestry, outlining his mostly happy and quite tumultuous life. Not many families have such a gift.

John’s nocturnal wanderings were a result of undiagnosed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. A condition that was not properly understood back then and was commonly called ‘shell shock’. He had spent three excruciating years in a Japanese Prisoner of War camp in Java during World War Two. He never talked about those terrible experiences. However, the night time incident made his family aware for the first time of the horrors he had survived.

Tim Jeal’s book about his father was finally published by Faber and Faber. The book was successful, serialised by The Times and featured as a BBC Radio 4 ‘Book of the Week’. Proving, to me at least, that chronicling the lives of every-day people by whatever method – acimostakewin, Instagram or scrapbooking – is of interest to others, as well as being a vital part of our personal history.

To read about some of our favourite celebrities’ family searches, and for suggestions to get your own search started –

Leave a comment